Infant colic may be amongst the most challenging and distressing conditions to manage – challenging for the healthcare professional, distressing for the caregiver(s) and infant.

Symptoms of Colic

Infant colic is defined by excessive crying behaviour, but can be accompanied by some or all of the following1-3:

- flushing of the face

- drawing in of the legs

- a rumbling stomach and flatulence

- difficulty sleeping

Crying tends to start in the first few weeks of life and happens mostly in the afternoon and evening, has no obvious cause and the infant appears to be in pain4.

Prevalence and Diagnosis

Experts agree the prevalence of infant colic is around 20% of all infants1.

To diagnose infant colic according to most recent Rome IV criteria, the crying episodes should last for 3 or more hours per day, for 3 or more times in a week5.

When it comes to diagnosing colic, the difficulty lies in deciding what constitutes ‘normal crying’ and ‘excessive crying’ for the infant. The Rome IV criteria also suggests encouraging caregivers to keep a 24-hour behaviour diary, which is helpful in ascertaining the total crying time in a 24 hour period is over 3 hours5.

Consequences of colic

When it comes to infant colic, it isn’t just the baby that is suffering - the consequences of colic on the mental health and wellbeing of parents should not be underestimated. Although generally the symptoms of colic will resolve over time, a parent’s decision to seek medical advice arises from a very real concern for the health of their child6.

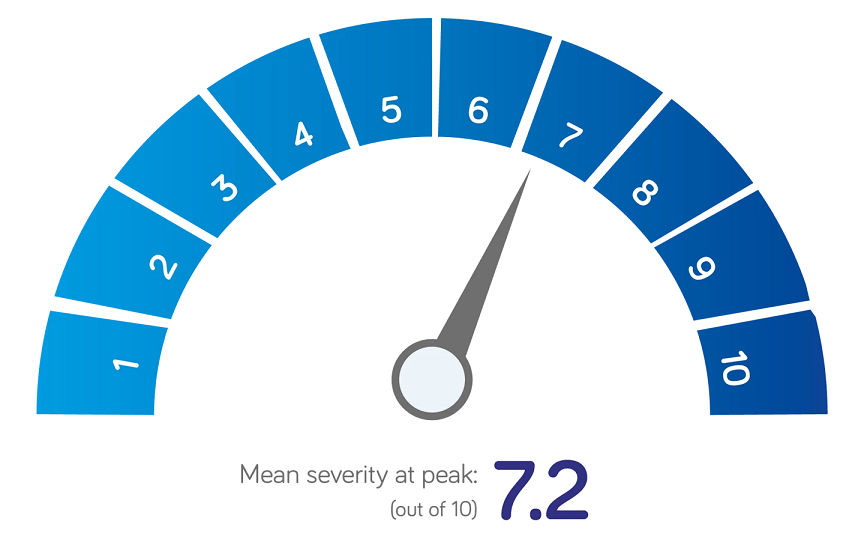

We interviewed 251 parents and asked them 'On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is not at all severe, and 10 is extremely severe, how would you describe your child's colic, when it was at its peak?'. The mean severity score was 7.27.

The same interviews showed that parents most frequently turn to Health Visitors for information on colic, with almost 2 in 3 parents seeking advice and support7. Parents also turn to GPs and Midwives for information, yet 2 out of 3 parents want more support from their Healthcare Professional when it comes to colic7.

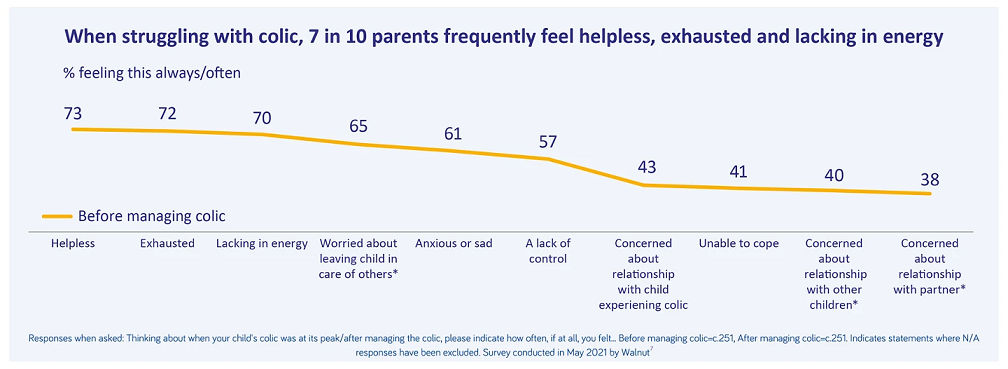

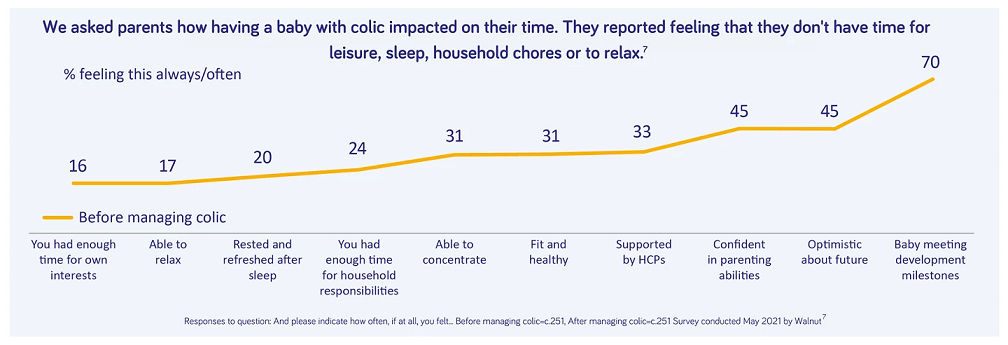

These interviews also found colic to negatively impact many aspects of parents’ quality of life7. At the peak of colic, parents reported feeling helpless, exhausted and lacking in energy7.

"We don't sleep enough, we are tired all the time and it is bad because we also have an older child of 3 years and we don't spend much time with her anymore

Other studies have found significant parental anxiety and stress if their baby had colic6,8, sometimes leading to loss of parental working days9 , and feeding changes such as premature breastfeeding cessation10

"I was feeling horrible. I am a single mum so it was extremely hard to handle. I had to call my friend a few times to come over and watch him for a few minutes so I can go to the shower and cry"

How to manage colic

Parents should be reassured that colic is a common condition in infancy, and usually resolves by 6 months11. However, parents are likely to be seeking strategies and guidance on how to manage the problem, which has driven them to their Healthcare Professional for advice and support.

First line treatments can involve practical ways to comfort the baby such as3:

- holding or cuddling baby during crying episodes

- keeping them upright after feeds

- frequent winding

- using a gentle rocking movement

- putting baby in a warm bath

- using some gentle white noise in the background

Healthcare professionals can also encourage parents/carers to look after their own wellbeing by11:

- seeking support from friends and family if they can

- sharing experiences with other parents

- trying to sleep whilst baby is sleeping

- taking a short time out if they feel over-whelmed, by putting baby safely in their cot for a few minutes

Recent interviews showed that parents’ feelings of wellbeing were significantly improved once colic symptoms were under control7.

"He had more sleep which meant us as parents had more sleep, meaning we had more energy to enjoy time with our older child too"

"I feel more relaxed and she can nap through the day. The house feels calmer and I have more time for myself"

Feeding considerations for colic

Breast-fed babies

NHS recommendations are to continue feeding baby as usual in the case of colic, so breastfeeding parents should be encouraged to continue with it wherever possible3 There is limited evidence for dietary modification for breastfeeding mothers in managing colic11, however, breastfeeding mothers may wish to try avoiding caffeine12. Breastfeeding mothers can be advised to try emptying one breast before changing, so that baby gets the benefit of the hindmilk which is richer in fat, which may help with digestion12.

Formula-fed babies

For formula-fed infants, a fast-flow teat can be tried.

Comfort formulas are an option that parents may wish to try. under the guidance of a healthcare professional.

In our interviews with 251 parents, many found comfort formulas useful to reduce crying episodes - reducing colic severity scores from 7.2 to 4 out of 10.

These parents also reported improvements in their wellbeing as a result of the reduction in Colic severity - ranking comfort milks as one of the most effective management options.7.

"Baby was happier and seemed to start bonding with her parents and sibling. Was able to show her more affection and get a happy response

"Everything seemed easier in the household"

Further support

Tools for healthcare professionals

Tools for parents and carers

- Vandenplas Y. et al. Gut health in early life: implication and management of gastrointestinal disorders. Essential Knowledge Briefing. Wiley, Chichester (2015)

- Savino F. Focus on infantile colic. Acta Paediatr 2007;96(9):1259-1264

- NHS. Colic. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/colic/ (Accessed July 2021)

- Daelemans S. Recent advances in understanding and managing infantile colic. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1426.

- Zeevenhooven J, Koppen IJ, Benninga MA. The New Rome IV Criteria for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Infants and Toddlers. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2017;20(1):1-13.

- Hyman PE et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1519-1526.

- Survey data collected from a nationally representative sample of 251 parents that reported their baby as having colic according to the ROME IV criteria. Survey conducted by Walnut May 2021.

- Vik T, Grote V, Escribano J, et al. Infantile colic, prolonged crying and maternal postnatal depression. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(8):1344-1348.

- Morris S et al. Economic evaluation of strategies for managing crying and sleeping problems. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:15-19

- Howard CR et al. Parental responses to infant crying and colic: the effect on breastfeeding duration. Breastfeed Med. 2006;1(3):146-155.

- NICE. CKS. Colic – infantile. 2017. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/colic-infantile/ (Accessed July 2021)

- HSE.ie. Colic in babies. Available at : https://www2.hse.ie/conditions/child-health/colic-in-babies.html (Accessed July 2021)